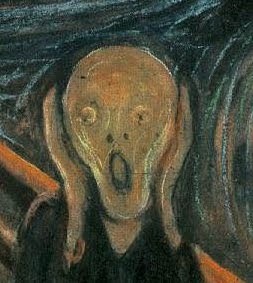

Recently I decided to gather some tips from food editors on what writers need to know to work with them successfully. I specifically asked them what freelancers should never say—what thoughtless comments make them want to scream and never want to hear from that writer again.

Recently I decided to gather some tips from food editors on what writers need to know to work with them successfully. I specifically asked them what freelancers should never say—what thoughtless comments make them want to scream and never want to hear from that writer again.

I was expecting most to complain about the lame excuses given for missing deadlines, but this was not among their top pet peeves. The cookbook editor in the group, Justin Schwartz, did comment on this topic, saying that so many writers missed manuscript deadlines he’d come to expect it! I know that newspaper editors must depend on their writers to deliver on time, but, still, none of them brought up this point.

Here’s what they did feel writers should NEVER say. The list (in random order) is quite revealing.

> “I’m not that familiar with your publication.”

Susie Middleton, the former editor and now editor-at-large for Fine Cooking magazine, thinks that the number one writer faux paux is saying even indirectly, “I’ve never read your magazine!” Joe Yonan, the Washington Post food and travel editor, agrees: “Anything that exposes ignorance about my publication or section [turns me off]. I recently got a writer query for Travel that said, ‘Do you do a ‘36-Hours-in’ feature? You know, like the one in the NYTimes?!” In short, if you show this little knowledge of or interest in the editor’s “baby” or bailiwick, you’re chances of writing for him or her are likely doomed.

What editors do want is strong evidence of just the opposite–that the writer knows the publication and what stories might be appropriate or inappropriate for it. Susie specifically warns against sending a proposal that would be, “perfect for Saveur when it’s actually going to Bon Appetit!”

She adds that every story idea needs to be tailored to the magazine’s mission–whether it’s how-to, entertaining, travel, or whatever. “The same recipe story could have five completely different angles depending on which magazine it’s going to,” she says. For example, a one-dish dinners story pitched to a magazine for young families would necessarily be entirely different from an entrees feature aimed at upscale empty nesters. The needs, interests, and tastes of these reader groups are just so different the recipes and focus would have to be as well. If you don’t target your idea appropriately, you will not only waste editors’ time but peeve them mightily.

> “My recipes don’t need editing.”

As surprising as it may seem, Wiley senior cookbook editor Justin Schwartz says that writers sometimes presume to tell him their work won’t need correcting or editing! His reaction: “I panic …. I’ve had people say they probably just need help crossing the t’s and dot the i’s, when I already know their recipes need massive reworking. They just don’t realize how bad their recipes are. They’ll say things like, “But my recipes really work–my fans tell me so.”

He’s particularly annoyed by claims about thorough recipe testing: “Frankly, I don’t understand how people can tell me they had other people test their recipes but then I find ingredients completely missing from the list or directions. Are their friends/testers just not mentioning the problems?”

Admitting that recipes aren’t tested thoroughly or that the written instructions don’t accurately reflect the writer’s testing procedure is also ill-advised. Says Eating Well senior editor Jessie Price: “I NEVER want a writer to tell me, ‘I didn’t actually test the recipe the way I submitted it…’ As in, I wrote instructions to grill something, but I actually just tested it under the broiler… Come on!”

>I want to write for you. Can you give me some topics?

Unless you have attained the status of contributing editor or are a long-time contributor to a publication, don’t ever ask editors to give you ideas to write about. They only parcel out assignments to those who’ve earned their trust. It’s your job to suggest ideas (and hopefully good ones) to them. Martha Holmberg sums up the general protocol this way: “A freelancer should never ask me what I’m looking for (at least until we have a longstanding relationship). I want the writer to tell me about something amazing that I don’t yet know, to be a resource for ideas.”

I know you said do X, but I did Y.

It’s the nature of the job for editors (especially of newspapers) to be perpetually harried and working on tight deadlines, so when they ask for specific material to be delivered in a certain fashion they really need the writer to comply. Often, they just don’t have time in the schedule to do a lot of extra editing; they tell you how to submit because they plan to use the material “as is” or as close to that as possible.

This is why Washington Post Deputy Food Editor Bonnie Benwick wants to scream whenever a writer tells her the following: “I know you said keep it short, but I had a lot to say. Just cut it to fit.” She’s not happy about this response either: “Instead of just answering your specific questions, I rewrote the whole thing.” The bottom line: Deliver exactly what’s asked for as asked for, not what’s easiest for you.

>”I’ve already sent this to X and Y [competing publications], but let me know if you want to use it.”

The Post’s Bonnie Benwick feels that suggesting something that you’ve already submitted to a competing publication is a nearly unforgivable sin. First, it’s insulting that another publication was approached first. Second, editors like to be sure that their content is exclusive and that there’s no chance it will turn up in a competitor’s pages. Image your reaction to seeing your fiercest rival show up in public wearing the same outfit as you and you’ll understand where they’re coming from on this.

Martha Holmberg, just recently named Editorial Director for Watershed Communications and previously food editor at The Oregonian in Portland is also touchy about the competing publications issue, adding: “A freelancer should never tell me that someone else’s deadline is more important than mine!” In other words, treat every editor and publication with dignity and respect, even if you feel you’ve got bigger fish to fry. IMHO, this is good advice in life in general, not just a wise approach to working with food editors.

If you’re an editor and I’ve missed one of your big peeves, feel free to sound off with what writers say that makes YOU want to scream. If you’re a writer, I’d love to hear if you found this list of “don’t”s helpful. Several other stories that might interest you: What Food Editors are (Still) Looking For, and Food Writing Lessons I’ve Learned the Hard Way.

Thanks for posting, Nancie. Greatly appreciate your feedback.

Excellent round-up of 'keys' to the door that we as writers want to unlock. Didn't feel like writer-bashing to me; it's a service to all concerned. Love strolling down the Kitchenlane with you, NB.

Interesting point Mark. I didn't intend the piece to have a "let's-pick-on-the-silly-writers," tone. But when I asked editors what got on their nerves I received some remarkably straight and revealing answers. And because I used most of what may sound like really harsh comments verbatim, it does lean in that direction. I could now do a story on what peeves writers about editors, but I'm not sure they'd be interested in reading it!

I agree that holding queries forever, or just never answering at all when the submission is obviously from a pro is very bad form. So is actually taking the query idea and giving it to another writer–which I know (from the other writer) has happened to me at least twice. But I also understand that most of the editors I know are good, concientious folks trying to do too much in too little time.

Great article, Nancy. So well researched–and so very true. But let me add something from the author side of things: I think it's very poor form when editors sit on proposals for six, seven, eight months. One publication where we are regular contributors will sit on proposals over a year. "We're still trying to fit it in." Any thoughts on that side of things?

There really isn't a good excuse for not reading the publication before pitching to an editor. That said, as an expat I wish my local library and bookstore had more English magazines to browse through. I either need to buy my own subscriptions which can add up or bring back magazines on my next trip to the States. Although I am sure it is not enough, how helpful is reading only the online version of the magazine for someone who wants to write for the paper edition? From my brief experience blogging for the Jerusalem Post writers were given only very basic guidelines. I am sure much more is expected from the regular staff.

Great post, Nancy! Thanks! Will be printing this out and keeping for future reference. This is definitely something we freelance writers need to read regularly just to remind us.

Thanks for your thoughtful comments Kevin. I don't have any experience with that particular situation, but I have found that sometimes what an editor told me she/he was looking for (or not) didn't seem to jibe with what the publication appeared to be doing. In one case, I later found that some major change in direction was underway, but not yet apparent in the issues of the magazine. In other cases, I agree–the editor and I just didn't speak the same language.

Nancy,

I hear and completely understand what Middleton is saying. But… I've pitched a few ideas to her and in each case it wasn't suitable for the publication. She was even kind enough to tell me why – which I greatly appreciated. Nevertheless, I've been a subscriber to Fine Cooking for more than five years and what she said she wanted simply didn't jive with what the magazine was doing. There was some link between her vision and the magazine's reality that I simply haven't been able to discover.

I'm NOT blaming Middleton. She has been exceptionally helpful. But sometimes writers and editors simply lack some common ground needed for communication. I say this as someone who'd been both an editor and writer for more than 20 years.

great article…going to share