Many Americans know and love the romanticized story of what we now refer to as the first Thanksgiving. I used to have such pleasant, if sappy, notions myself, at least partly due to having seen Norman Rockwellish artworks like those here. You know–the ones kissed with golden light, filled with beautiful, abundant tables, and depicting two different peoples happily engaged in cross-cultural mingling.

But having delved into American culinary history, I’ve realized that very often the popular images don’t jibe with the facts. The artists (who were working several centuries after the actual event) conveyed their own personal vision, embellishing, omitting, and filling in details as desired. So, a lot of what we think we know about the so-called first Thanksgiving is either wrong or slightly off. I think it’s important to correct a few mistaken impressions because, honestly, the truth is much more poignant, compelling, and thought-provoking than the myths. Among other things, it reveals just how tenuous the Colonists’ situation was.

Look closely at these paintings and see if you can spot any of the liberties taken with the facts. Hint: Note who was there, what they wore, what they ate, and what they were doing. I picked up on some of the problems after reading the fascinating firsthand accounts of the settlers in a remarkable work known as Mourt’s Relation. Here are just a few myths, followed up with a few relevant facts.

Myth: The Pilgrims set out a fine harvest celebration spread, kindly invited neighboring Native Americans to join in, and everybody sat down to a fancy feast.

Myth: The Pilgrims set out a fine harvest celebration spread, kindly invited neighboring Native Americans to join in, and everybody sat down to a fancy feast.

Truth: Conditions on the Mayflower and then at Plymouth plantation were so harsh that at least 45 of the original 102 colonists had died of exposure, malnutrition, or disease by the time the history-making gathering occurred. It’s highly doubtful that the settlers had fine tureens, eating utensils, etc.; or enough tables and benches to seat a crowd; or the wherewithal to decorate with cheerful squashes and sheaves of grain. There was probably a table for the “dignitaries,” and, because it was considered uncouth to eat on bare wood, the surface would have been covered with a cloth of some kind. But it’s likely that most participants ate (and stayed warm) simply standing around the campfire or roasting pit used to cook the meal.

Myth: The two groups met peacefully in equal numbers with the immigrants and Wampanoag mixing freely and celebrating joyfully.

Truth: A letter written to a friend by settler E. W. (probably Edward Winslow) recounts that when several Colonists began jubilantly celebrating the harvest by shooting off their weapons, about 90 local Wampanoag tribesmen, including their leader, Massasoit, showed up. (Historians think about 50,000 Wampanoag may have lived in the area.) Winslow seems to imply that the Indians were not invited but simply came to investigate the gunfire. A vital misrepresentation in all three of these paintings also casts the event in an entirely different light: In fact, the Colonists (about 50 in all) were outnumbered by their guests nearly two to one! They may well have felt uneasy and pressured into making a friendly gesture of offering to share a meal.

Additionally, given that the Pilgrim females, including children, numbered only about 15, it’s likely that the hostesses were just overwhelmed preparing and serving food, not mingling or sitting enjoying a meal. (Some beleaguered Thanksgiving hostesses today might say that nothing hasn’t changed!)

Myth: The original Thanksgiving menu featured huge roast turkeys, accompanied by cornbread, oysters (shown shucked in the forefront of the painting at right), cranberry sauce, and pumpkin pie.

Myth: The original Thanksgiving menu featured huge roast turkeys, accompanied by cornbread, oysters (shown shucked in the forefront of the painting at right), cranberry sauce, and pumpkin pie.

Truth: Yes, most of us understand that our modern Thanksgiving menu is largely symbolic and that the original feast may not have included “all the trimmings” with the turkey. In fact, while turkey is nearly always spotlighted in paintings of the event, there is no absolute proof it was on the menu. We know for sure that poultry was eaten because the Governor sent four men out “fowling,” and their hunt “served the company almost a week.” But the fowl may have been ducks or geese. In addition, the featured meat during the feasting was almost certainly venison, as Mourt’s Relation suggests: “… the Indians …. went out and killed five deer, which they brought… and bestowed upon our Governor….”

As for the various sides we now think of as Thanksgiving must-haves, historians say that corn, pumpkins and similar winter squashes, cranberries, and seafood were all part of the Wampanoag diet, and eventually they were also eaten by the newcomers. But cranberry sauce and pumpkin pie were probably not part of that first celebration because the Colonists had meager provisions with no sugar to sweeten dishes or flour to make pastry dough. (Colonists were definitely eating cranberry sauce with game later in the century; check out my post and pics on cranberries here.)

Myth: The Pilgrim men wore mostly black and big, shiny buckles, and the native Americans were shirtless and sported their traditional feathered headdresses.

Truth: Historians say that neither the dress of the Pilgrims nor the Wampanoag is accurately depicted in these images. The artists simply wanted to suggest an earlier era, and dark clothing and buckles had once been in fashion but at the time were considered quaint. Knowing little about various native American cultures, the painters just threw in assorted stereotypical “Indian” touches like feathers and scant clothes. In fact, experts point out, their details hinted at the dress of certain Plains Indians, not those tribes who inhabited the American Northeast.

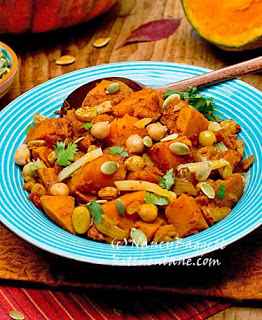

Moroccan-Style Spiced Winter Squash Stew

I make no claims that the following squash dish was enjoyed at the first Thanksgiving. I can say that it takes advantage of one of our most bountiful fall vegetables, is tasty and colorful, and will fit well in a holiday meal. It could serve as a main dish for vegetarians.

I make no claims that the following squash dish was enjoyed at the first Thanksgiving. I can say that it takes advantage of one of our most bountiful fall vegetables, is tasty and colorful, and will fit well in a holiday meal. It could serve as a main dish for vegetarians.

The squash in the background of the pic is called Fairytale, and it is the tastiest eating squash I know. Some farmers’ markets sell it, but otherwise it is hard to find. The readily available butternut is a good alternative.

If you have fresh gingerroot on hand, add 1 teaspoon peeled and very finely chopped when the dried spices are incorporated for an even livelier, richer flavor. Also, if you are a fan of Moroccan food and happen to keep preserved lemons around, serve them, chopped, in a condiment bowl along with the finished stew.

Tip: This dish includes a Moroccan blend of spices called has el hanout. Specialty shops sometimes carry ready-to-use classic versions of it, and, if desired, you can substitute 1 to 1 ½ tablespoons for the list of spices specified here. Of course, the flavor of your dish will depend on what particular spices were in the blend purchased.

- About 1¼ pounds winter squash (butternut, fairytale, acorn or other similar squash)

- 2 teaspoons olive oil

- 1 cup peeled, chopped onion

- 1 teaspoon each ground coriander and ground ginger

- ½ teaspoon each ground turmeric and ground cumin

- Pinch hot red pepper flakes or more to taste

- 1 14.5 ounce can diced tomatoes including juice (plain or seasoned with green chiles)

- ⅓ cup seedless golden or brown raisins

- ¼ teaspoon salt, or more to taste

- 1 15.5 ounce can garbanzo beans, rinsed well and drained

- Fresh lemon wedges and fresh chopped coriander leaves for serving, plus chopped preserved lemons and pumpkin seeds, optional

- Cut the squash into 3 or 4 large chunks.

- Place slightly separated on a microwave safe plate.

- Top with a microwave cover or wax paper.

- Microwave on high power, stopping and testing in the thickest parts with a fork at 5 minutes and then 1 minute intervals until the flesh is just barely soft enough to cut into cubes.

- Set aside until cool, then peel away the skin and cut the flesh into 1-inch cubes.

- You should have 3½ to 4 cups; reserve any extra for another purpose.

- Heat the olive oil and onion in a deep 12- or 13-inch skillet over medium heat, stirring.

- Cook the onion, stirring, about 4 minutes or until lightly browned.

- Add the squash, coriander, ginger, turmeric, cumin and red pepper, stirring until the squash cubes are coated with the spices.

- Stir in the tomatoes, raisins and garbano beans.

- Adjust the heat so the mixture boils gently and cook, uncovered, until the squash pieces are just tender and the liquid has boiled down.

- Taste and add salt, then serve; or store refrigerated in a non-reactive container and reheat at serving time.

- Provide lemon wedges and chopped coriander leaves so diners can garnish their servings as desired.

- Offer pumpkin seeds and preserved lemon also, if desired.

Other classic dishes you might like for Thanksgiving: A yummy Pumpkin-Cranberry Bread Pudding.

Or how about Cranberry-White Chocolate Drop Cookies? Or perhaps a surprisingly delicious Autumn Bisque?

I'm always looking for a holiday side dish that can also serve as a main dish when vegetarians come, so I like this a lot. Sorry you aren't a squash fan!

Your information debunking the first Thanksgiving paintings is priceless! I think I got my false impressions from grade school. Don't you remember drawing pictures of the supposed happy gathering? I had never thought about details like the tablecloths in the paintings.

Squash has never been a big favorite of mine. I do like Moroccan-style dishes, though.

This dish would fit in any fall or winter menu–maybe you can try it after the big feast? I make it fairly often cause it's good and good for me 🙂

I really like the squash stew recipe, I wish I woulda found it sooner for this years feast….

Next year for sure!